In celebration of our 25th anniversary, WiRED is pleased to bring you stories from our archives. These articles provide a glimpse of WiRED’s early work as they depict the places and the projects we have focused on over the years.

In 2001, WiRED received a developmental grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) to determine if computers could deliver health information in low-resource Kenyan communities. While in the West we were slowly building computers into our daily routines, people in the needy countries we served had rarely seen one. NIH’s charge to WiRED was: Can computers teach people about HIV/AIDS and good health? Answering that became the focus of our early work in Kenya.

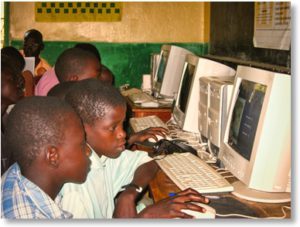

After months of research and preparation, WiRED trained and deployed a team of more than 60 staffers who provided computer training, health guidance and language translations in 23 Computer Health Information Centers (CHICs) throughout Kenya. The free-to-all centers opened from 8:00 to 5:00 every weekday, each stocked with a half-dozen computers and a wide assortment of CD-ROMs bearing health information and training programs. People could walk in, sit at a computer and, with the guidance of a staffer, learn basic computer skills needed to access the health information. Clearly, the computers were the initial draw — seeing and working this new technology was a huge attraction.

The NIH question about the capacity of computers to educate people about health raised a series of other questions critical to our work. We needed to know: if people could be drawn to the information rather than just to the computers; if the computer presentation of HIV/AIDS and health information could interest users enough to engage them in the content; if people had confidence in the information on the computer; if people would show up at all? Imagine if we put in months of work, trained a dedicated staff and, at some expense, brought in many computers, then nobody showed up!

This archived story answers all these questions. It was written by Barbara Yates, an American nurse who, working with other NGOs, was providing assistance to the Kenyan medical community. Barbara volunteered to help WiRED with a variety of tasks in the early days of our CHIC program. After visiting a number of our new facilities, she wrote this compelling, first-person story clearly addressing all our questions about the computer-based CHIC health education program.

From 2001

WiRED’s Community Health Information Centers:

Evidence of Impact at The Grass Roots

by Barbara Yates, R.N. WiRED Volunteer

It was a typical equatorial day, sunny and warm, as we started our site visits with a stop at a Center outside the Kajiado district where the Masai people live. These dirt roads are unmarked, and we thought we took a wrong turn until we saw the tin-roofed hut ahead and the people standing outside to greet us. We stepped from the van to the smiles, hand clasps, introductions and greetings: “Habara?” (how are you?), “Karibu.” (Welcome), “Karibuni!” (Welcome all!). As we entered the building we could feel the pride of the people in their Center. Our visit coincided with a visit of the Kenyan Ministry of Health representative, Dr. Risa Kurarru, himself a Masai. We could see his excitement as he witnessed how the Center was providing previously unavailable medical information not only about HIV/AIDS but about a wide range of health concerns in the region.

It was the same at all the Centers we visited — big smiles, warm greetings, involvement of the people, pride in the Center. Okay, there was lots of pride and excitement, but are the Centers having a real impact on the people? Research data held the empirical answer, but even a casual observer can clearly see it.

It was the same at all the Centers we visited — big smiles, warm greetings, involvement of the people, pride in the Center. Okay, there was lots of pride and excitement, but are the Centers having a real impact on the people? Research data held the empirical answer, but even a casual observer can clearly see it.

In Kisumu, medical students were using the Center for research, doctors and nurses were using it to upgrade their professional expertise. That’s good news, but apart from medical professionals, what about others in the communities? The answer is yes, the Centers are serving a much broader audience as well.

Youth Peer Educators come regularly to review the disks covering sexually transmitted disease. The disks have enabled them to recognize symptoms, and this has lead the peer educators to promote awareness among youth, which, in turn, has lead to increased diagnosis and treatment among young people in the region. Moreover, the Peer Educators told others. Village women came to the Centers and told other women. Even commercial sex workers were visiting, viewing the HIV/AIDS discs and going for voluntary testing.

In Butula we were amazed to see the traditional healers (who we had met on our first visit) arrive barefoot, soaked from the heavy rain to keep their regular Wednesday and Friday schedule; this was Wednesday. We observed as one of the volunteers patiently translated the information on the Alternative Medicine disc to them.

We were told they have been bringing in samples of herbs, holding them up to the screen, identifying them, noting uses listed on the disc and offering to each other their own uses as well. They also brought their private remedies for use against joint pain, skin conditions and other ailments.

Peer Educators came for a three day training session over the school break, and they have plans to come with groups of five to ten youth on week-ends. We were told by the adults visiting the Center that there is a noticeable change in the youth of the community. Whereas they used to “hang out” at the village dukas (small shops) increasingly they are coming to the Center and what they have learned has helped reduce their involvement in risky behaviors. This is particularly important in light of a recent survey which revealed that 50 percent of youth in the area-as young as 10-years old–were sexually active.

Peer Educators came for a three day training session over the school break, and they have plans to come with groups of five to ten youth on week-ends. We were told by the adults visiting the Center that there is a noticeable change in the youth of the community. Whereas they used to “hang out” at the village dukas (small shops) increasingly they are coming to the Center and what they have learned has helped reduce their involvement in risky behaviors. This is particularly important in light of a recent survey which revealed that 50 percent of youth in the area-as young as 10-years old–were sexually active.

Teachers are using the HIV/AIDS files for additional information to add to the required HIV/AIDS curriculum just initiated throughout Kenya. Local public health officers–to fulfill their requirement to alert people to the dangers of HIV/AIDS–are also visiting the Centers to increase their own knowledge. For them, the Community Health Information Centers are a primary source of information. The Ministry of Health representative in charge of the Busia district described the Centers as “a unique strategy of information dissemination” and expressed hope that another Center would be set up in the district headquarters’ main hospital.

In Kilifi, where there was an early concern about how to attract a largely illiterate population that held strongly to traditions has witnessed an astronomical increase in the number of visitors. Hundreds visit each week. Beach operators (those who live off tourists who use their services), led by a 58 year old man, have formed a group of 51 men who regularly make use of the HIV/AIDS and STD discs. On their own initiative, they are developing a program to inform others.

In Kilifi, where there was an early concern about how to attract a largely illiterate population that held strongly to traditions has witnessed an astronomical increase in the number of visitors. Hundreds visit each week. Beach operators (those who live off tourists who use their services), led by a 58 year old man, have formed a group of 51 men who regularly make use of the HIV/AIDS and STD discs. On their own initiative, they are developing a program to inform others.

On top of all this, medical professionals and teachers have asked the Centers to remain open on evenings and week-ends so that they might have further access. All the Centers have agreed voluntarily to give more of their time.

So, the question: Are the Centers having an impact? From this nurses’ viewpoint, they are having more of an impact that we could have imagined.